I’ve moved! You can find my new website at www.micahchampion.com. I’ve re-envisioned, revamped, and reconstructed it. So come on over.

Inktober 2016

Jake Parker started the Inktober Initiative in 2009 to, as he puts it, “improve my inking skills and develop positive drawing habits.” Its grown into a world-spanning event of thousands of participating artists. This year I took on the challenge myself to produce one inked drawing everyday of October and I think I did pretty well.

I posted the drawings on my Instagram account following the prompts on the Inktober website. I fell behind here and there due to the inexorable march of life but caught up to finish on time. I have to admit, while I’m pleased with producing something everyday, I’m not entirely proud of all I produced. Instagram responded well, though, and I picked up some followers thanks to Inktober. I’d like to keep the momentum going, though maybe not at the same pace.

So, let me thank Jake Parker for creating awesome experience of Inktober and to all of you that followed and encouraged me along the way.

The Rundown

We’re well into autumn here in the Great Northwest. The weather is a little wetter, the air a little crisper, and school is back into full swing. I had a great summer and I look back on it with a kind of nostalgia. The season was a do-over of sorts from last summer when my cancer diagnosis tossed my family and I into an emotional tumult. And boy, how I enjoyed it and I’m sorry to see it go.

As I’ve stated before, I’m resuscitating, revamping, and reinventing my art career. How? Well, for one thing, I set the simple goal of attending the Rose City Comic Convention in Portland, present my work to the greatest number of art pros, collect feedback, and assess my next step.

The convention was great and I learned a lot. The first lesson I learned was that I’m not a very good businessman with lots of room to improve. The good news is what I lack is information. I’m not totally out of my depth, thankfully. I gathered a good chunk of information at Rose City and the implementation is attainable with some hard work and a little luck.

Second, pro artists are great. Everyone I asked to look over my work did so graciously. A few times, even, when I thought I was taking up too much of their time, they wouldn’t let me leave until they gave me their full feedback.

The feedback itself was largely positive with a lot of constructive criticism peppered throughout. It gave me a lot of confidence to continue working and, with better business practices, create a nice little niche for myself in the wider art world. In practical terms, this means more comic pages, an improved website, prints for sale, and a better presence in the next year at conventions. Chad and I continue to work on our creator-owned property The Brood which we hope to finish and shop around to publisher or distribute ourselves in the near future.

Thank you for your time. More to come.

Your Brain In A Vat

When the French philosopher and mathematician Rene Descartes published his Meditations on First Philosophy in 1641 he inadvertently created a science-fiction/fantasy sub-genre. How? The Mediator (Descartes’ narrator) methodically reasons from known falsehoods he once believed to the unreliability of his sensory perception, and finally concludes that abstract truths such as mathematics could be false. Why? According to The Mediator it’s possible that an omnipotent demon could be preying upon his mind and senses, feeding him falsehood built upon falsehood.

This idea of false reality is not original to Descartes. It dates back to the dawn of human history from Gnostic religious movements like Greek and Roman dualism, Taoism, and Buddhism. Belief systems supposing that the material world is inferior or illusory, and that our senses in fact obscure this reality, existed well before the philosopher. However, Descartes’ innovation was to uncouple this false reality from the salvation, or gnosis, of any particular religious or philosophical path. Enter the Cartesian nightmare.

Now, there’s so much more to the concept of “learned doubt” that Descartes offers. I will exclude here how he attempts to answer this doubt and the further responses and criticisms of other philosophers. But, for storytellers, this nightmare provides incredible and intriguing potentialities.

Victims of a false reality usually play the story’s heroes. Descartes’ demon is greater in evil than even the evilest of evil corporations manipulating world markets and orchestrating the rise and fall of nations. The Matrix’s (1999) villains and or the Black Mercy in the Superman story For the Man Who Has Everything intrinsically communicate evil to the audience because they harness all human connection, emotional and rational, to their own ends. Your life is a lie but only they know it.

In my mind, the major problem with nearly all of these stories is motivation. Why bother, really? Yes, a mad scientist could trick the a man into believing he sits under a tree when his brain is in fact submerged in slimy liquids, diodes suction-cupped to the prefrontal cortex, and no such thing as a “tree” actually existing. But why? A ‘humans as batteries’ plot is insufficient. The villains are sentient machines with flying squid ships. Nuclear clouds obscuring the sun seems much less difficult an obstacle compared with the expense required to keep humankind bottled up. Just sayin’.

Even when a story’s plot doesn’t rest on this “Brain in the Vat” premise, the characters in any story inhabit a vat of their own kind. We, as their storytellers, put them through their paces to expand our horizons, stretch our imaginations, and entertain ourselves and others. There is no hope of them knowing they live in a false reality unless we enlighten them. We make them fly on the backs of dragons when no such things exist. When we write stories, we reverse the roles. We become Descartes’ demon, creating our character’s realities for our own entertainment.

Whenever you or I create a story we invest ourselves in an imaginary world with our experiences, emotions, and, yes, even our rational minds. If successful, a story maintains the “suspension of disbelief,” which we readily volunteer the moment we step in line to purchase the tickets, buy the book, or download the media. Only afterward, if at all, do we reevaluate a story to scrutinize a character’s strange or deficient motivations or plot holes that jack the wheels off a storyline.

We have incomplete knowledge, so creating a story that’s both competent and compelling requires a lot of skill to mask over those deficiencies. Every story bends, but hopefully doesn’t break, under the falsehoods we inevitably weave into our narratives.

It just makes me wonder what glaring plot hole makes my life story so unbelievable to those watching me.

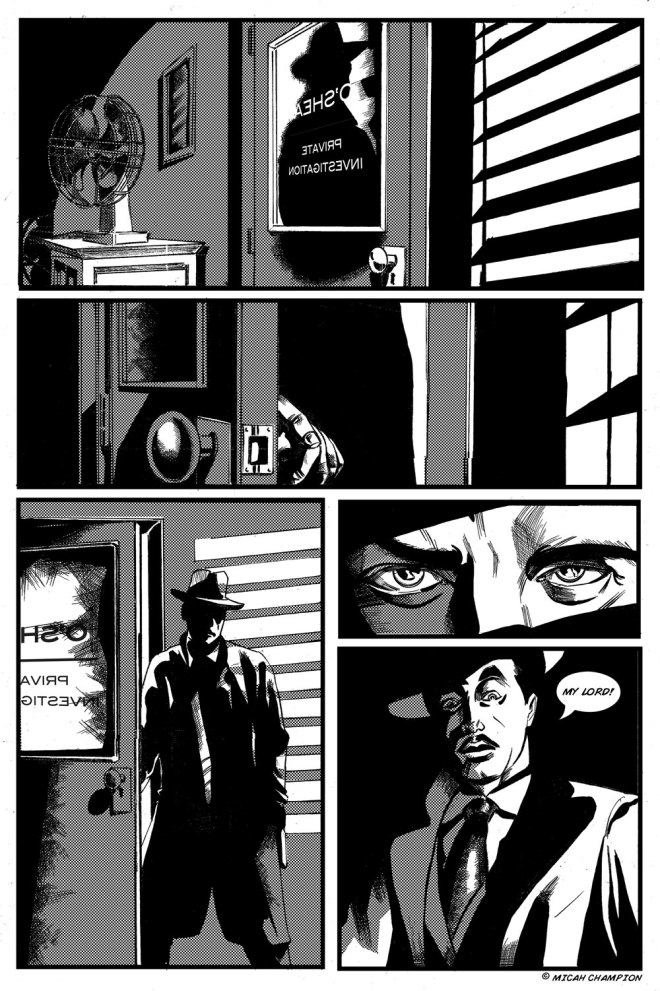

The Easy Descent #3

This is page 3. Hope you enjoy.

The Easy Descent #2

I finished up the second page of my web comic and here it is:

There won’t be a post next week due to the annual family camping trip. Enjoy that sun.

The Easy Descent

Summer is here and, like most transitions, I have bumped along the road of so many assumptions that I arrived at my destination late. I missed my post last week and a day late this week because schools out, the children stay up late, wake late, and remain restless all day. The time to stamp out a post on anything, well, is short.

But, nevertheless, I made it.

This week I am few on words and long on pictures. I have teased myself quit awhile with the opportunity to write/draw a noir-ish detective story like so many of my favorite writers. My character, Rick O’Shea (a horrible homonym that I enjoy all the same), is my detective and this story his first case you (the reader) and I (the writer) bear witness to.

I have outlined most of the story, written only a few pages, and drawn just one. My reasoning for posting the one page now, as opposed to waiting until closer to completion, is twofold. First, I just need to do it. I sat and contrived the story and characters a number of times, over the past several years, and never pull the trigger. Maybe fear or timidity kept me from sharing or, perhaps, just perfectionism stood in the way. After cancer, little seems precious to me in the light of my life and relationships. Perfectionism is no longer a goal and timidity a small hobgoblin to step over.

Second, this is an experiment. I’m not a writer, but an admirer of writers. I do not expect this to rise to level of classic or, even, competent storytelling. Consequently, I hope for interaction, input, and criticism. This is an opportunity to learn and improve as an artist by putting on the habit of a writer. I enjoy stories of all kinds and variations. Mine and your life, itself, spools out like a tangle of knotted, unruly threads that, gathered together, create a rich tapestry of the human story. How better to learn than to try?

The title is The Easy Descent. I hope you enjoy.

To Grads From Dads

Father’s day is weird. The creation of Mother’s day took off immediately by historical standards from its creation by Anna Jarvis in 1905 to its signing in 1914 by Woodrow Wilson into a national holiday. By contrast, Father’s day taxied up to the runway moments after Mother’s day, bounced along in fits and starts for some 50 years until LBJ gave it the all clear and then Nixon finally let it take off in 1972. It seems like the NIT of holidays, the runt of an already packed litter of American holidays. And, I think, deep down inside nearly every committed father sort of knows it too. The comedian Jim Gaffigan, father of five, developed a whole bit on the oddity of the holiday.

This sense of misplaced priority stems, I think, from the seemingly inverse correlation between how well your father raised you and how much you talk about your father, especially as an adult. Fathers are analogous to the CIA in that you only hear about them when they have really screwed up. The sting felt by so many men, women, and children by fathers that never showed up or, when they did, made their children’s lives a living hell is always present in some soul tearing sort of way. Taking a day to honor fathers spotlights a job well done that regularly operates best when the children are unaware.

Dads learn quickly that fathering garners little of your children’s adulation in the moment. To be sure, kids love their dad and, even, admire him, but they also know him as the grumpy guy that takes toys away and makes them clean up and, oh, makes you stand around holding the wrench for when he needs it. A good father has to both treat his children with the respect they deserve and also like uninformed halfwits so they won’t get hurt. Yes, a good father should love their child unconditionally, but everything else, from general hygiene to choosing a spouse, is graded.

Now, I love my dad. He’s a great guy and an excellent father. My siblings and I enjoyed him playing with us, spending time with us, and all the affection he showered on us; but many of those positive feelings I developed for him only happened after I became an adult, then a husband, and finally a father myself. My dad taught me how to work hard, delay gratification, and treat others with dignity and respect. Sure, he failed me sometimes, but that only helped him demonstrate that humility and forgiveness outstrip anything stubbornness and pride might have to offer. Consequently, some of his best moments as a father are the moments I liked him the least. And, I can’t thank him enough.

So, anytime a man treats a woman with respect, even when she does not treat herself with respect–that’s Father’s day to me. When an athlete shows grit and sportsmanship after she loses the big game–that’s Father’s day to me. When a teenager buys her first car after working all year, squirreling her away her earnings–that’s Father’s day to me. After a young man has made a mess of his life and he decides to turn the corner, takes responsibility for his actions and cleans himself up–that’s Father’s day to me. And, after four years, putting off partying with her friends on the weekend to study, she celebrates after she graduates–that’s Father’s day.

Happy Father’s Day to all those grads!

The Simple Art of Murder

My wife, Jessica, enrolled in a “Detective Lit” course some seventeen years ago now. Our marriage was so new at that time she could have returned me and received a full refund. But, to my continual delight, she instead concentrated her efforts on finishing off her bachelor’s degree so we might then earn glorious amounts of money and never hit so much as a speed bump for the rest of our lives. Jess loved the course and took enough notes to prove it. The course was not exhaustive, but covered the early greats of the genre–Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and Ross MacDonald. I had read a mystery here and there, mostly Sherlock Holmes and Encyclopedia Brown, but had never read any story populated by icy blondes, a revolver in their garter belts, or men dressed in well-cut serge suits, with hard eyes and wine-red ties, before in my life. Then, as soon as Jess put a book down, I picked it up to dog-ear it all over again.

The style, Chandler’s particularly, grabbed me. Loose, witty, and sometimes whimsical, all the while characters talked over the corpses of dead men, it seemed effortless and fun; a casual way to speak about sordid matters without losing your sense of humor. Chandler wrote of

“Hammett’s style at its worst was as formalized as a page of Marius the Epicurean; at its best it could say almost anything. I believe this style, which does not belong to Hammett or to anybody, but is the American Language (and not even exclusively that any more), can say things he did not know how to say, or feel the need of saying.”

And, indeed, every sentence dazzled me with novelty.

The stories, too, seemed to live in their own reality (maybe a less fanciful reality had I read this fiction out of a 1930s printing of Black Mask magazine) and the people in them seemed to live lives larger than their duty to the plot. In Raymond Chandler’s essay The Simple Art of Murder, published in 1944, he runs through the formalization of the mystery genre, pithily fencing in the land it always had to graze.

“…fundamentally it is the same careful grouping of suspects, the same utterly incomprehensible trick of how somebody stabbed Mrs. Pottington Postlethwaite III with the solid platinum poniard just as she flatted on the top note of the “Bell Song” from Lakme in the presence of fifteen ill-assorted guests; the same ingenue in fur-trimmed pajamas screaming in the night to make the company pop in and out of doors and bull up the timetable; the same moody silence next day as they sit around sipping Singapore slings and sneering at each other, while the flatfeet crawl to and fro under the Persian rugs, with their derby hats on.”

The formal problem, usually presented as murder, was really beside the point. Hammett’s Sam Spade, Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, or MacDonald’s Lew Archer spent most their time negotiating the psychology of the man or woman standing in front of them, who likely held or concealed a gun and attempted to either intimidate them or tempt them. Mystery novels, love them, answer all their own questions. The detective story, on the other hand, was something entirely new to me; rarely answering anything succinctly and always leaving overlapping penumbras lingering in my mind.

We keep these books, the originals Jess bought for the course and additions, in a box. I get a hankering around the end of Spring/beginning of Summer for a good detective book, so I dig these literal gems out to read again. I always start by rereading Chandler’s essay on the genre and then shuffle through the volumes to sample the flavors of each writer. Do I want to start with the brute efficiency of Hammett’s prose? Or, the deadpan, slow burn of Raymond Chandler’s wisecracking charm other writers frequently strain to imitate? Or, Ross MacDonald, staring into the philosophical depths of Lew Archer’s soul while he punches a chisler in the gut for pulling a switchblade on him?

Whatever I decide, you should pick one of these books up because not only is it about crime and honor, a principled man standing against a society gone to seed, but its literary art. And as Raymond Chandler wrote:

“In everything that can be called art there is a quality of redemption.”

Best Supporting Character

If you’ve every had the pleasure of watching Tombstone (1993), you would be forgiven if you thought the movie was about Doc Holliday and his pal, Wyatt Earp. Nearly every memorable scene in that movie is graced by a sweaty, pallid countenance of Doc Holliday (Val Kilmer) delivering a delightfully cunning line. The climactic finale of the film isn’t between Johnny Ringo (Michael Biehn) and Earp (Kurt Russell), but concludes, as any good Western should, with Ringo and Holliday dueling. When I walked out of the theater in 1993, I wanted to be Doc Holiday, not Wyatt Earp. I wanted to be the supporting character, not the lead.

Yes, he stole nearly every scene, but Holliday received second billing despite his nihilistic bravado and the virtuosity of his gun-play. He proclaims his supporting role clearly and concisely several times over the course of the film. “Wyatt is my friend,” he says after another member of Earp’s posse when asked why he is there and not in bed. He’s a gambler, gunfighter, killer, and terminal drunk, but held high above all those moral and physical shortcomings he is Wyatt’s friend. We, the audience, watch him stab a man over a card game as introduction to his character at the beginning of the movie. He promptly leaves with the loot he underhandedly won to move on to greener pastures. Only when the life of his friend is threatened does he become part of a greater story.

The Unassuming Type

Let me describe the next character. He’s a decorated war veteran and a crack shot. Also, he’s a surgeon, a gifted writer with a sly sense of humor, and lends his assistance to the cause of justice whenever possible. Pretty impressive. We could deduce that he’s a brave, intelligent, creative, an enjoyable person to hang around, and possesses high moral character. He’s a first-rate character. But, like Holliday, he’s a supporting character. He doesn’t embark on his own adventures, instead spending his time accompanying an eccentric, drug-abusing, intellectual that regularly inconveniences him and sometimes treats him like an imbecile. He is, of course, Dr. John H. Watson.

His honor, friendship, and discretion keep him from stepping out from Sherlock Holmes’s shadow. As a consequence, Watson appears slow-witted in contrast to the sometimes maniac genius of his partner and, as Holmes’ biographer, he’s delegated himself to aiding and recording another man’s career and life. No one has confused Dr. Watson as the main character in the adventures of Sherlock Holmes, though his character, on the merits, is much more impressive than the genteel cutthroat Doc Holliday.

Show Your Support

These two types of characters seem to have little to relate them except their secondary nature to the story and the main character. But if you look closer, you’ll notice that they both, in their own way, they’re both important, nudging or cajoling their respective leads onto the right path. Doc’s death wish and unwavering friendship protect Wyatt Earp whose too invested in hunting down his brother’s killers to turn away from a gun duel he’s no hope of winning. Dr. Watson keeps Holmes’ life from derailing with a large doses of common sense and care, of which his friend’s genius seemingly strips him. To be precise, they keep the story going.

In my life, I’m the protagonist. I’m the lead that walks through the story of my days. When dealing with cancer this notion was acute, watching my family, friends, and complete strangers come to my aid. Conversely, I’m the supporting character in many, many more stories and to many, many more leads. My wife lived through my time in chemotherapy as the hero in her own story, struggling to meet the material, emotional, and spiritual needs of our family all the while taking care of me. Everyday children ride the bus I drive to school as the little hero in their own coming-of-age story. I have the greater opportunity to play an out-sized or unassuming role in the lives of others than I do in my own life.

But, like Doc Holiday and Dr. Watson, I have the opportunity to be important without it being about me.